Why do C-Loop lashings not work with excessively wide cargo?

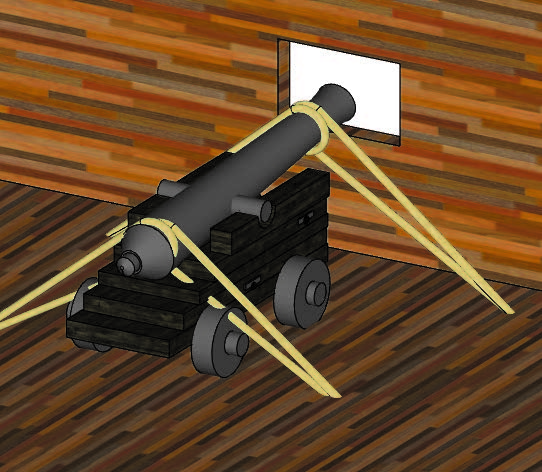

Loop lashings, in addition to many other techniques of attaching lashings, have been around for centuries, once used for securing cannons on ships to provide additional storm protection, today loop lashings are used for a wide range of purposes.

Vertical loop lashing is known internationally as the C-loop. The C-loop generally works well when the cargo is narrower than the means of transport to which the lashings are attached.

Such securing has always worked very well, so why does it no longer work well in all situations?

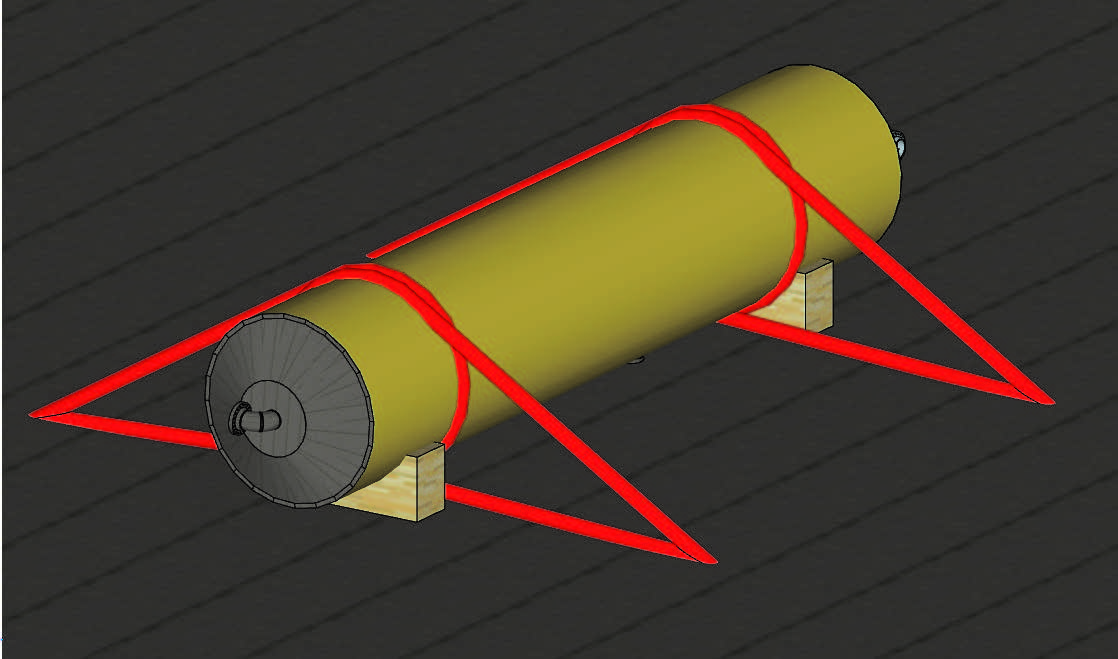

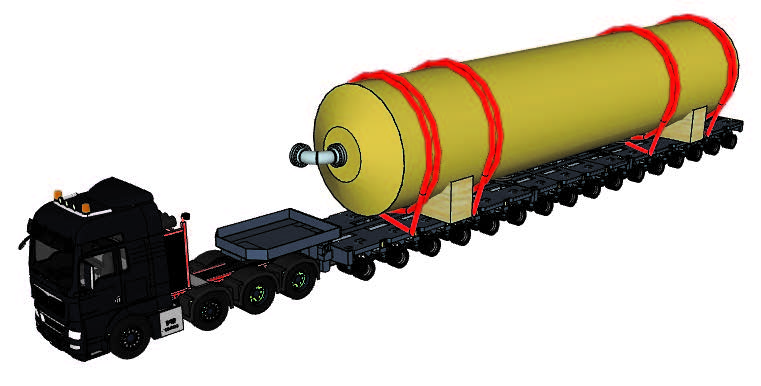

The clear answer is: our standardised means of transport are limited in width and thus are often too narrow for the loads that have grown in size. If, for example, a column such as the one shown above is placed on a flat rack or a truck, it often looks like this:

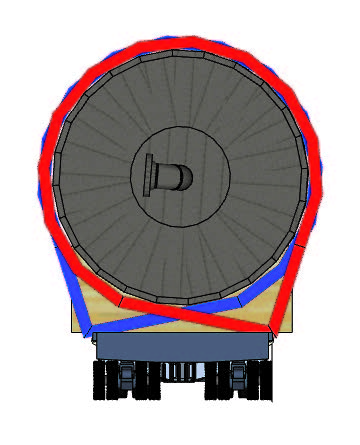

From this perspective, it looks quite alright. However, seen from a different perspective, it is evident that these "C-loops" do not work well:

The red loop does not secure the cargo against movement to the left because in order to do so, both ends of the belt would have to be pulled in the same direction (see above illustration of the column secured in the vessel). As this sketch shows, however, the right end of the belt is directed to the right side (as seen from the attachment point of the lashing) and thus loses its retention force.

This becomes even clearer with an extra-wide case (here is an example of a case on a flat rack); only one belt is considered here for the sake of clarity:

The excess width of the cargo compared to the load carrier is evident.

The green belt is actually intended to prevent the case from sliding to the left.

In order for the case to be able to slide to the left, the belt has to make more room available on the left-hand side.

But where is this additional room supposed to come from?

At the beginning of the sliding phase, the belt frees up the necessary room on the right side due to the excess width.

This means that on the right side, the required slack forms in the belt which is needed on the other side to provide more room for the case.

It is not until the cargo is flush with the edge of the load carrier on the right that the belt starts to work on the left side.

However, at this point, the cargo has already reached a speed that can no longer be stopped by the belt.

(We have to keep in mind that cargo securing can only hold a load in position, it cannot stop a load already in motion).

Therefore, it is only now that the belt enters the stretching phase. The belt will fail…

…

... which will ultimately result in cargo damage.

In many cases, the cargo of other parties and/or the load carrier also sustain damage as a result of inadequate cargo securing.

The result then looks like this:

Before:

After:

After the salvage:

Calculations have even shown that a pair of C-loops is only as effective as a single tie-down lashing in the case of cargo with excessive width and is also less cost-effective.

TF = 500.00 kg

µ = 0.3

α = 30°

LC = 1.8 TF µ sin(α)

LC = 135.00 kg

TF = 500.00 kg

µ = 0.3

α1 = 30° and α2 = 1.6°

LC = 2 TF µ (sin(α1) + 0.8* sin(α2))

LC = 157.00 kg

We must therefore conclude that C-loops are no more effective than a single tie-down lashing in the case of excessively wide loads.

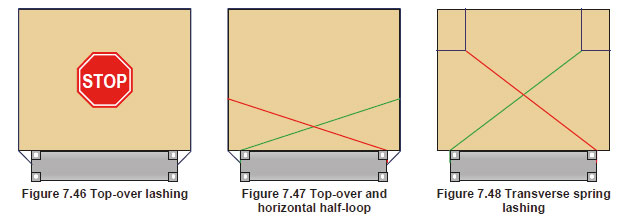

Reference is also made here to the CTU Code, which clearly shows that such cargo securing is not advisable:

If the cargo has a smaller width than the load carrier, C-loops have a completely different effect and can be used very effectively as direct cargo-securing, just like for Hornblower's cannons.